You can download here a presentation of breton language situation. You can also download the file that the Mercator network has requested from OPAB update in 2019.

Breton : a Celtic language

Breton, the only Celtic language spoken on the continent

The Celtic languages, like Romance languages and Germanic languages, are Indo-European languages.

Today they are spoken in Ireland, Scotland, the Isle of Man, Wales, Cornwall and Brittany. Cornish and Welsh are the languages most-closely related to Breton, the only Celtic language spoken in continental Europe. The Celtic languages, and especially Breton, are related to the Gaulish language, now extinct.

Four dialects are usually identified in Breton : cornouaillais, léonard, trégorrois and vannetais. The names of those dialects correspond to the 4 dioceses of Lower Brittany. However, there is no clear-cut division between dialects that could prevent understanding. Throughout the 20th century, due to the development of bilingual education, the media and a modern Breton-language literature, a common language has emerged, with fewer local variations. Today, speakers under 50 can read and write their language and they easily understand each other.

Breton, a unique language

Breton is a full-fledged language, as far as grammar, syntax or lexicon are concerned. Word order is flexible, for instance, the main element of information is emphasized and placed first.

The settlement of Britons in Armorica

Breton comes from the island of Britain

The Celtic peoples who migrated to Armorica from the 5th century B.C. onwards brought with them their own language : Gaulish. It was spoken there until the end of the Roman Empire, even if Armorica had been quite Romanised, by that time.

Later, migrations from Wales, Devon and Cornwall, were to ‘recelticize’ Armorica. Britons crossed over the Channel at the beginning of the Middle Ages (5th and 6th centuries) and settled down in the peninsula, giving it its new name, Brittany.

The new settlers brought great changes to Armorica. They stamped their presence by naming their settlements : plou (parish) as, for instance, in the name of Plougastell-Daoulaz, gwik (the middle of the parish) as in Gwimilio, lann (monastery, oratory) as in Lannuon, tre (inhabited place, village, ‘treve’, succursal church) as in Trevendel, lez (court, palace) as in Lesneven, bod (mansion, residence) as in Bodsorc’hel…

Declining after blooming

In the 9th century, the Breton state reached its peak. Bretons invaded parts of Normandy and Anjou. The capital of the kingdom was placed in the East side of Brittany, in the non Breton-speaking part of the country. The language of the elite was Latin, or rather Romance. Little by little the Breton language recessed westwards, and three different areas emerged :

in the East, Brittania Romana, an area where the Breton-speaking settelements were always in small numbers. Breton was to disappear soon;

in the East, Brittania Romana, an area where the Breton-speaking settelements were always in small numbers. Breton was to disappear soon;

west line Saint-Brieuc/Saint-Nazaire, Brittania Celtica, where the Breton language was to prevail;

and in the middle, a mixed area, where both languages were used and where the Romance language was eventually to prevail.

In the 16th century, the linguistic border came to a halt on a North-South line, from Saint-Brieuc to Saint-Nazaire. Today this linguistic border tends to disappear as standard French has spread everywhere and the Breton language has become a symbol of identity for all Bretons.

A thriving language

Breton as a medium of education

Since the 19th century Bretons have struggled for the recognition of their language by the ministries, according to the wishes of the people, but they have been confronted to the refusal of the Minister for Education.

Parents then decided to create their own schools where Breton would be the means of education. The first Diwan school opened in 1977. Breton-French bilingual classes were then opened in public schools (1982) and in private Catholic schools (1991).

The figure of 15,000 pupils educated in bilingual classes (Diwan, public schools, Catholic schools) was reached in September 2013.

Besides, around 13,000 pupils are taught Breton as a subjec.

A professional asset

Breton classes for adults are quite popular too and they concern almost 3,500 people.

Recently, knowing Breton has become a professional asset to get a job. More than 1,200 jobs now require Breton speakers, either in schools, in the media, in associations, in services, in local jobs…

Breton, a language for the 21st century

Some local authorities are engaged in programmes to promote the use of Breton in their fields of power. The Breton language conquers new areas, like trading, media, advertising, computing, banking… Ofis ar Brezhoneg, with its « Ya d’ar brezhoneg » campaign, encourages and enhances those initiatives, in the private sector as well as among local authorities. Breton is the main Celtic language used on Wikipedia, which shows that the language is well established in the 21st century. Facebook, OpenOffice, Skype, Mozilla, FireFox and Thunderbird softwares all have Breton versions.

A new attitude

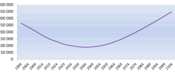

The number of Breton-speakers is still decreasing but, thanks to the growing number of bilingual schools, there are more and more young people who can speak the language. In the same way, activities like dancing, acting, singing (kan-ha-diskan) are full of life and cultural enthusiasm. The Breton language has wide support and it is used more and more in public life.

- Accueil

- |

- Plan du site

- |

- Contact

- |

- Crédit

- |

- Mentions légales

- |